The sun rises in the east: Philippines’ startup breakout moment (Fintech Perspectives)

29 March, 2022

2023 Outlook — Fintech everything everywhere all at once

1 February, 2023

One Step Closer to a Digital Pakistan

3 July, 2022

Over the last few years, the global digital banking industry has gained prominence and is projected to reach $30.1b by 2026, with digital banks in some parts of the world already proving to be successful (e.g. China’s WeBank and Brazil’s NuBank).

In Southeast Asia, many countries have joined the digital bank party — Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and recently Thailand. In South Asia, Pakistan is the latest to announce a new digital banking regulatory framework in January 2022. With South Asia being a secondary geographical focus for us at Integra, we’ve taken the opportunity to jump a little deeper into the developing digital banking landscape in Pakistan (we invested in two Pakistan-based startups so far, Udhaar Book back in 2021, and MedznMore¹ in 2022 ). We believe there is huge potential here — considering its 220m+ population, the ongoing transition to a digital economy and the relatively low valuations compared to markets like Indonesia. As one of the youngest countries in the world with a median age of 22.8 years, about 49% of the population being English speakers, and over 300k IT professionals, Pakistan is home to driven entrepreneurs and tech-savvy individuals who are leading the drive for increased digital adoption.

In this article, we will be zooming in on:

- The new digital banking regulatory framework in Pakistan

- Market opportunity #1: Why the digital banking licensing framework is important for Pakistan

- Market opportunity #2: Why the digital banking licensing framework is interesting for investors and startups

- Market opportunity #3: Why digital banks’ journey ahead may be challenging in Pakistan

- Summing up the big picture: What’s next for digital banking applicants

Pakistan’s new digital banking regulatory framework

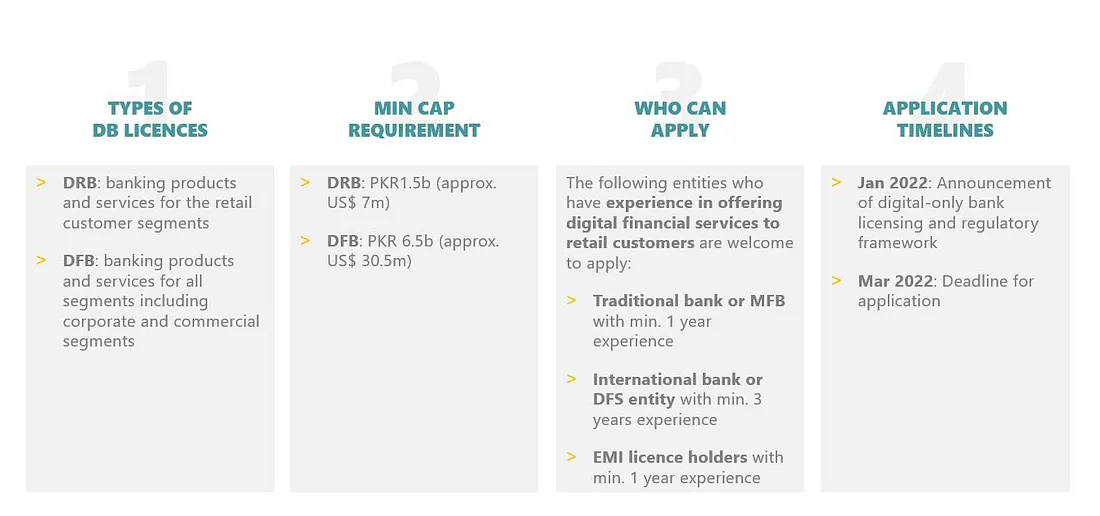

The new digital banking regulatory framework was announced in January 2022 by the State Bank of Pakistan (“SBP”) and there will be up to 5 licences issued. Figure 1 below shows a summary of the regulatory framework.

Currently, there are other digital payment licences in the country — the PSO/PSP² licence for payment gateways, the EMI³ licence for e-wallet providers and the NBFC⁴ licence for financial institutions providing selected financial services e.g. lending. The ability to engage in the business of banking, i.e., accepting deposits for the purpose of investments and lending is what sets the digital bank licence apart from the other digital payment licences.

Why the digital banking licencing framework is important for Pakistan

SBP has implemented various frameworks and initiatives for Pakistan to go digital — standard QR codes, NADRA’s digital ID, Raast (PK’s instant payment system)… and many more. These initiatives are relatively new, however, and adoption is still low and slow. The digital bank licence paves the way for the next crucial step for the country because: 1) Pakistanis’ preference to use cash for transactions, 2) the large proportion of unbanked population and existing credit gap, and 3) the current fragmented payments processes available.

- Cash-predominant market: Pakistanis are infamous for their preference to transact in cash — Digital transactions make up only 0.2% of Pakistan’s $100b transactions. This is a huge problem as it results in inefficient processes and promotes rampant tax evasion.

- Unbanked economy: Pakistan continues to be among the top 3 unbanked economies in the world⁵ by absolute population size — 70%⁶ of the 221 million population are unbanked, and women make up 93% of the unbanked population. In addition, less than 1%⁷ has access to credit cards and only 15%⁸ had access to formal credit in 2017. SMEs also only get a meagre 5% in banking credit despite contributing over 30% to the country’s GDP⁹. At the same time, Pakistan is one of the youngest countries in the world where approximately 60% of the population is in the 15–29 age bracket¹⁰ which represents the target group for digital adoption.

- Clunky payment processes: The digital banking services offered by traditional banks in Pakistan are not as seamless as those we see in other countries. For instance, Singapore’s PayNow enables users to do real-time fund transfers with just a mobile number. On the contrary, users in Pakistan have to register the intended recipient’s bank accounts first before transferring the funds, which makes user experience slow and painful. This problem is easily solved by tech-enabled digital banks.

The digital cost efficiencies and conveniences of digital banks that drive financial inclusion for the unbanked and underserved segments are generally well understood.

But those benefits may not count for as much in a country where the traditional banks are already highly digitised. For example, in Thailand, the incumbent banks (e.g. Siam Commercial Bank and Kasikornbank) have invested heavily in digital financial services, reducing the disruption caused by digital banks. Digital banks become much more valuable in a country like Pakistan where the traditional banks are slow at digital adoption.

Why the digital banking licencing framework is interesting for investors and startups

The ability of digital banks to acquire unbanked Pakistanis and the opportunity to fill up the credit gap in the country sums up a huge market opportunity with significant revenue potential. The deposit base available to digital banks that can be used to provide low-cost capital for lending is a huge advantage over other credit players that have to resort to higher cost funding. With the high number of unbanked and underserved population, coupled with access to rich digital ecosystems of customer data, the opportunity for lending to this customer segment becomes massive. On top of that, Pakistani banks’ deposit base has been growing at a much higher pace compared to its GDP. This presents a timely opportunity for digital banks to address the credit gap in Pakistan.

The good news is…. Pakistan is simultaneously experiencing a massive boom in its tech startup scene. The article by Rest of World pointed out the VC funding frenzy in Pakistan: $366m in VC funding in 2021, which was more than every previous year combined. This gives an opportunity for fintech startups like TAG to serve the large underbanked population.

How big is the market potential exactly? Our internal market sizing exercise estimated the total addressable market for deposit base and lending to be $166b and $95b. It is unsurprising why investors and startups alike are watching the space closely.

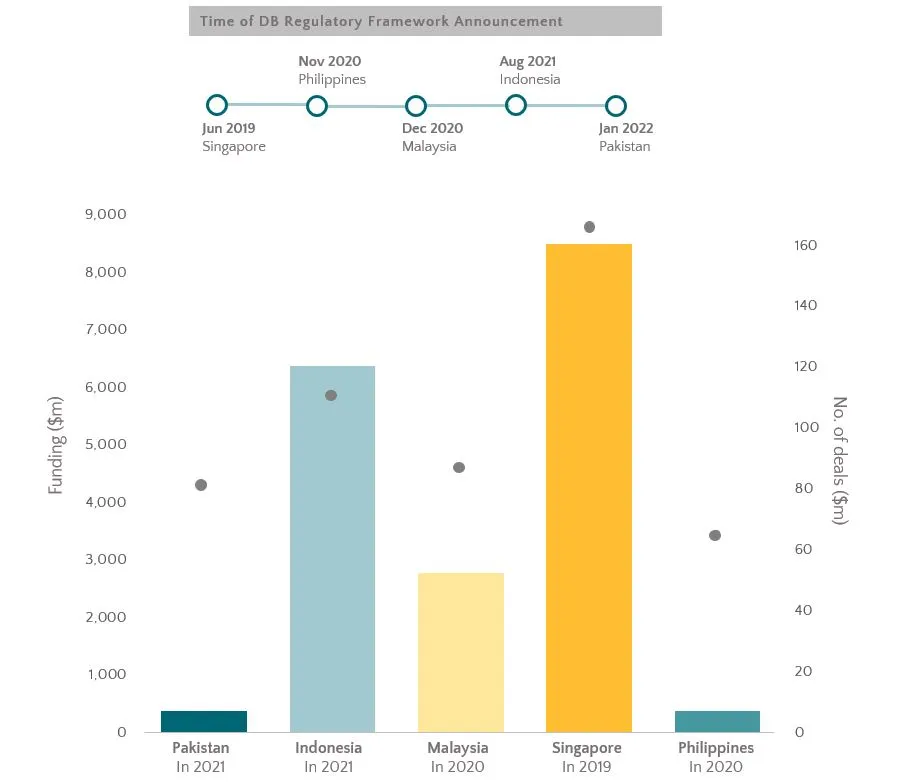

Figure 2 below compares VC funding volumes (shown in bar chart) and total number of deals (shown in dots) in respective countries post the digital banking regulatory framework announcement. At the point when digital banking systems were announced, the tech startup ecosystems in both Pakistan and the Philippines were at a far more nascent stage compared to the rest of Southeast Asia — which gives digital banks in those countries far more room to capture value from those ecosystems. That’s where the huge upside potential for digital banks in Pakistan and the Philippines lies — to gain a much larger market share in the digital financial services space due to the lack of alternative dominant players in the space. (For Philippines, see our previously published insights piece on the Philippines tech breakthrough moment).

Figure 2: Funding volume (shown in bar chart) and number of deals (shown as dots) in Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, SIngapore and Philippines in the year when the digital banking regulatory framework was announced. Source: https://restofworld.org/2022/pakistan-tech-investment-boom/, Statista, The Straits Times, Foxmont Capital & Boston Consulting Group Philippine VC Report 2022, Pitchbook, DealStreetAsia, TechNode Global

But is Pakistan ready for digital banks?

Why digital banks’ journey ahead may be challenging

All this makes digital banks seem like they will be the next unicorns in the country, but the journey ahead might not be as smooth sailing as most expect.

First, geopolitical concerns remain an issue for investors heading into Pakistan. Political and economic instabilities render the country’s ecosystem un-ideal for startups’ growth. Currency depreciation of the PKR against the USD also remains a concern for foreign investors and may affect startups’ scalability.

Second, the existing infrastructure is not yet mature enough to support digital banks. Most of SBP’s initiatives e.g. the real-time payment rails, Raast, is still relatively early and delayed. In contrast, India’s UPI currently dominates the digital payments space in India with 22b transactions in 2020–2021. In addition, the internet infrastructure in Pakistan is lacking, particularly in rural areas. Internet and smartphone penetration remain low, making customer acquisition challenging for digital banks.

Third, there is the cultural belief that is deep-rooted in Pakistanis, particularly that surrounding women. The segregation between sexes has caused women to have limited mobility and to be excluded from financial decision making. Opening a bank account is not a norm for women in the country because it would require women to interact with a customer service representative who is likely to be male. Digital banks are able to solve this problem by offering a seamless, fully digital customer onboarding process. But many Pakistani women do not have the liberty to own a mobile phone or have access to the internet which makes it challenging for digital banks to acquire female consumers. On the bright side, efforts and initiatives have been made by the authorities to close the gender gap, the success of which will ease up customer acquisition for digital banks.

Summing up the big picture: What’s next for the digital banking applicants?

All in all, the market opportunity for digital banks as well as some of the challenges the players may encounter have been highlighted above. SBP stated that it received 20 successful applicants and has given in-principle approval to various entities to commence a pilot.

There are, however, a lot more conditions to fulfil before a digital bank gets its licence approved, which begs the question: which players will lead the space in the years to come?