2024 in Review: Key Startup Trends and Predictions for 2025 in Southeast Asia

16 December, 2024

Voluntary Carbon Markets: Up From the Bottom

1 April, 2025

The problem is Demand, Not Supply

In early 2023 when voluntary carbon markets (“VCM”) were booming, a damning investigation by Guardian revealed that more than 90% of offset credits certified by Verra, the world’s leading standard for the voluntary carbon markets, were worthless “phantom credits” that did not represent genuine climate benefits. Prior advances were quickly overturned. Demand evaporated. In just a year, the transaction value of the voluntary markets shrank by 61%.

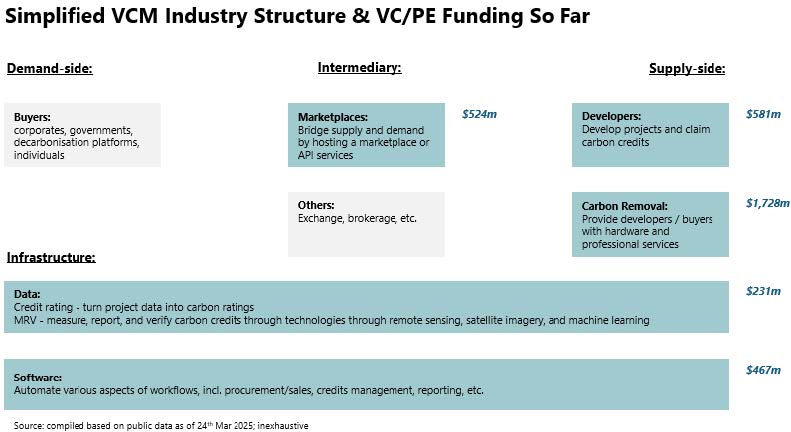

In 2024, a new wave of startups emerged from the debris, raising over $1.3 billion in total. Well capitalized, they dove into fixing supply quality, which had been the proximate cause of the market collapse still fresh in memory. But ~1,000 million tons of market surplus - defined as the difference between credits issued and credits purchased - is too large to be entirely attributed to quality deficiencies.

What are Carbon Credits, Really?

People tend to make the argument for voluntary carbon credit markets in various ways:

- They serve as financing vehicles that mobilise capital for “climatic returns”. The rise in value of carbon credits creates the economic incentive for more capital to be directed towards actions that address climate change.

- They reduce the friction from what would otherwise be an extremely painful, operationally complex process for companies to reduce their carbon footprints, or get to net zero.

Let’s examine this one by one.

Voluntary Carbon Markets as Economic Incentives

Any first-year economics student would know that markets - and price - is a derivative of demand (and supply) and not an inherent source of demand itself. Of course, in the short term, price behavior can certainly catalyze behavioral changes - hence market bubbles and crashes. But this is rarely sustainable in the long run. Under normal conditions, voluntary carbon markets are a mechanism for doing good. But they do not create the demand for good themselves.

Reducing Friction

Can reducing friction be the way to catalyze demand? Uber, for example, demonstrated how the market for a good or service can balloon if technology removes friction from the process, inventing a whole new market for transportation - ride hailing - simply by making it easy to book a taxi on demand. And many argue that voluntary carbon markets serve a similar function. Credits are an exponentially easier way for companies to claim progress towards net zero, when compared to the hard yards of re-examining supply chains or re-designing manufacturing processes.

But while the new experience of ride hailing met pent-up demand from people who were frustrated with poor public transportation, who did not want to drive, or who did not want to cadge rides from friends - it did not create demand for transportation itself. Reducing friction unlocks demand, but it does not create it from scratch (or only marginally so). So the question is if the voluntary carbon markets can be sustained simply by addressing reactive and opportunistic demand from corporates who, if left alone, would be disposed to avoid such spending altogether - if that marginal demand created out of circumstances is large or small, fickle and short-term or sustained and permanent. In physics at least, at a low initial velocity, friction has less impact on the final velocity.

So What Needs to Happen?

In effect, what we are saying is that carbon emissions are a textbook case of the tragedy of the commons, where markets fail to price in the negative externality of emissions. But that issue cannot be resolved by a trading market for voluntary carbon credits that is disconnected from the markets for the economic activities that create that pollution - the market for food, housing, transportation, and so on. The true demand catalyst has to be regulation that marries the two markets together, or which introduces the element of regulated demand from the compliance markets into voluntary markets.

Today, voluntary and compliance markets are structured into separate and distinct markets, despite their theoretical complementarity. Without a globally consistent standard, allowing voluntary credits to be traded at parity with allowance units could flood the market with cheap voluntary credits and undercut the incentive to reduce emissions in the first place. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement is a key change agent to watch. By allowing countries to trade carbon credits to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions and providing a universal framework, it incentivises and enables governments - especially in developed countries - to incorporate voluntary markets into their national decarbonization schemes. In this model, VCM will be used to offset emissions beyond the mandated cap, serving as an additional lever to compel the internalisation of negative externality. While uncertainty around the timeline remains, the recent agreement on crediting methodology marks a critical step towards the full operationalization of Article 6.

Where to Invest Then?

Developers: go beyond tech-enabled

Project development represents the bulk of market revenue simply due to cost base. The real question is around economic profit.

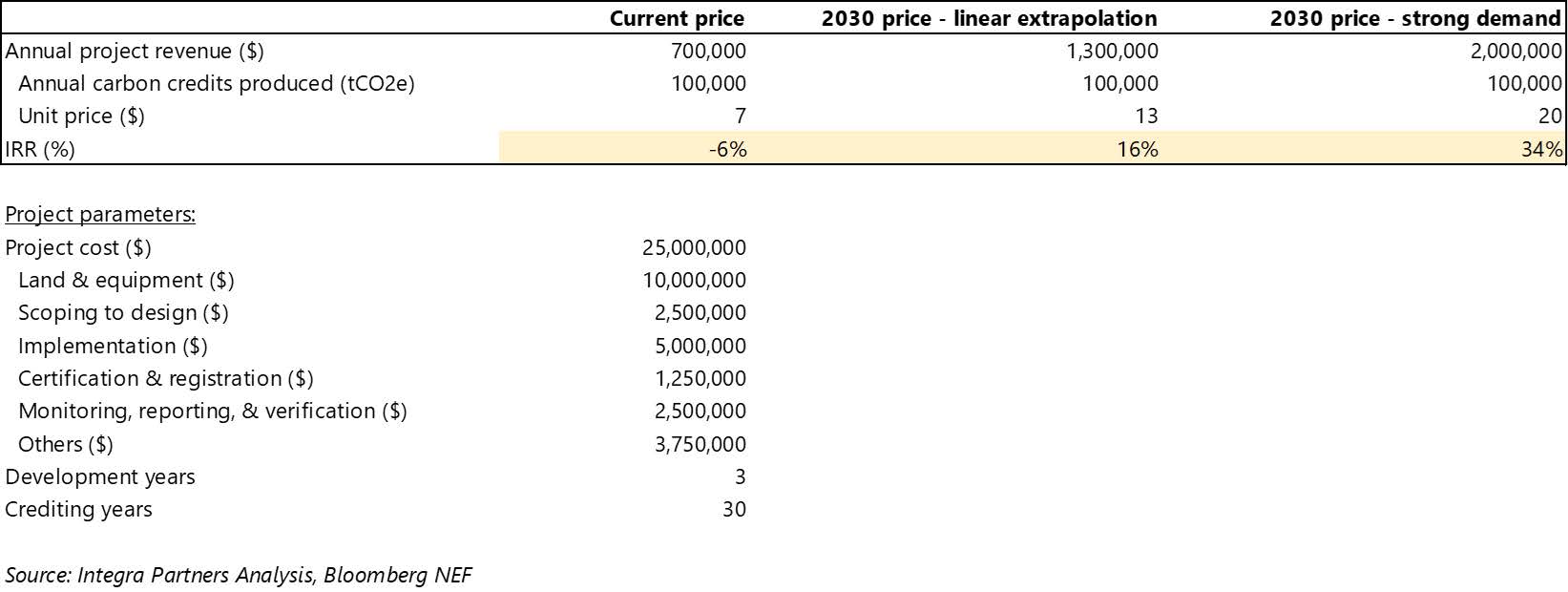

Traditionally, project development relies on boots on the ground, and the incremental number of boots per new project does not decrease meaningfully with scale, thus the low operating leverage and natural fragmentation. For instance, in one sample contract we reviewed, the project developer actually loses money at the current price point, even under generous assumptions of full upfront payment and zero operational cost during the crediting years. The poor economics explain the sector’s heavy reliance on grants and subsidised loans.

A project-level IRR only meets the typical return hurdle of venture capital at $20 per tCO2e, nearly 3x of the current price. Yet underwriting an investment on price speculation is hard, regardless of one’s personal belief. The other possible lever is development efficiency. While a new generation of tech-enabled developers is springing up, the perfunctory use of third-party technologies alone leads to only incremental efficiency improvement and ephemeral competitive edge at best. To generate venture-style returns, a full-stack reconstruction of the development process - with proprietary technologies and interdependent architectures - is almost a prerequisite.

Carbon removal: distinguish between scientific experiments and viable businesses

Technology-based solutions (“TBS”) like direct air capture are exciting scientific advancements that fundamentally enhance the permanence of storage.

However, working scientifically is one thing, working economically at scale is quite another. While TBS projects accounted for 12% of capital raised from 2021-2025, the investments translated to less than 1% of credits delivered due to high costs, physical constraints, and regulatory risks involved.

Trying to pick winners during waves of technological experiments is humbling. When evaluating a potential investment in the space, we ask ourselves the following questions to be less wrong:

- Does the underlying science plausibly lead to a radically better performance?

- Is the deployment relatively free of physical and regulatory constraints?

- At what scale does unit economics start to make sense?

- How much capital is needed?

- Does the business model allow the company to unlock that capital through compelling adoption drivers such as additional revenue streams, modular deployment, and etc.?

Marketplace: timing matters

Love is blind, and even more so when it comes to venture capital and marketplaces. Marketplaces are inherently prone to winner-take-all dynamics, have little technology risk, and sidestep most of the pesky risks of operating in the real world. This makes them particularly appealing to venture capital. In carbon markets, however, things have gone awry. No player seems to have gained meaningful traction to date, and the overall capital efficiency has been dismal.

Marketplaces do not necessarily mean good businesses. Here, due to perceived homogeneity among credits, the marginal value per new project diminishes quickly. Also, as a small number of corporates are responsible for disproportionate transactions on the network, the marketplaces’ ability to retain value is limited.

For marketplaces to truly take off, VCM needs to first mature to a point where long-tail demand becomes significant enough. The last will be the first.

Data: still niche but evolving favourably

Despite calls for accurate data to restore trust, the market remains niche - with only a select few players surpassing $1m in ARR.

Today, the use of geospatial data is largely confined to preliminary screening and due diligence, which are far removed from credit issuance. As a result, the willingness to pay remains generally low. One promising signal is that the standards are moving to accept direct biomass estimation into their methodologies. It is worth observing the development.

Another nuance is that because geospatial data is uniquely esoteric and obscure, the perception of quality is as important as quality itself in this field. To scale, startups need to go the extra mile to translate data into intuitive formats and engage with key distribution partners strategically.

Conclusion

Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere just reached 800,000-years high. Our time calls for a thriving VCM. Though the present moment might be marked by noise, volatility, and frictions, they are temporary distortions. Over a longer time horizon, patterns clarify, momentum builds, and systems resolve. We look forward to partnering with the ambitious founders who will shape this next chapter in the decades to come.

Written by Guanwei Wang, Analyst at Integra Partners.